It was very early in the morning, perhaps around 6:00am, when our accommodation let us know that our driver was here to pick us up. We brought our luggage down the stairs and two men very quickly loaded up the car. We had both a driver and a guide who would take care of us for the whole day as we made our way to the city of Huế. We had flagged to the accommodation that we would need breakfast, so the driver and guide immediately started looking out on the streets for any banh mi stall open. The driver sped around, desperately trying to locate one. It was amusing from our side because we had never seen someone take the quest for food so seriously. Finally, we spotted a snoozy stall. The guide helped me order a vegetarian banh mi, and then we were on our way.

It took about an hour to reach our first stop of the day, Mỹ Sơn Sanctuary. Mỹ Sơn Sanctuary dates from the 4th to the 13th centuries CE. It was the religious and political capital of the Champa Kingdom for most of its existence. In 1999, the sanctuary was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Chams, or Champa people, are an Austronesian ethnic group in Southeast Asia as well as an indigenous people of central Vietnam. They are the original inhabitants of coastal areas in Vietnam and Cambodia, along the South China Sea, since before the arrival of the Cambodians and Vietnamese.

From the 2nd century CE, the Cham founded Champa, a collection of independent Hindu-Buddhist principalities in what is now central and southern Vietnam. This ancient kingdom emerged in the late 2nd century and reached its peak in the 9th and 10th centuries. After that, it gradually declined and was annexed into Vietnam in the early 19th century.

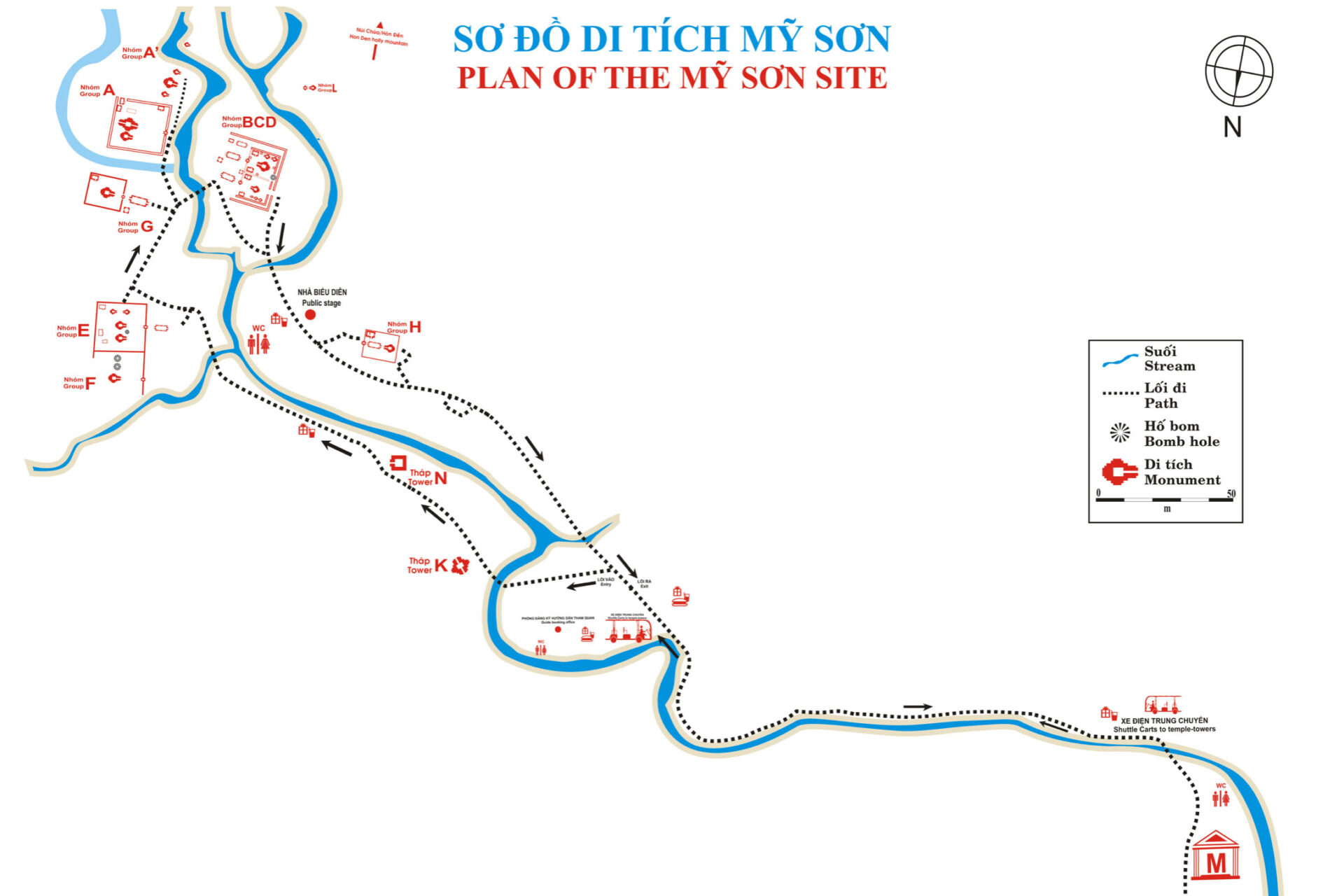

I’m not sure if it was because it was early, or because our tour guide charmed the driver, but we were driven up the road and then onto the pedestrian-only part to get as close as possible to the site. The drive saved us about 30 minutes of walking uphill! The map just below shows the long path you go along until you reach the clusters of buildings.

I’m not sure if it was because it was early, or because our tour guide charmed the driver, but we were driven up the road and then onto the pedestrian-only part to get as close as possible to the site. The drive saved us about 30 minutes of walking uphill! The map just below shows the long path you go along until you reach the clusters of buildings.

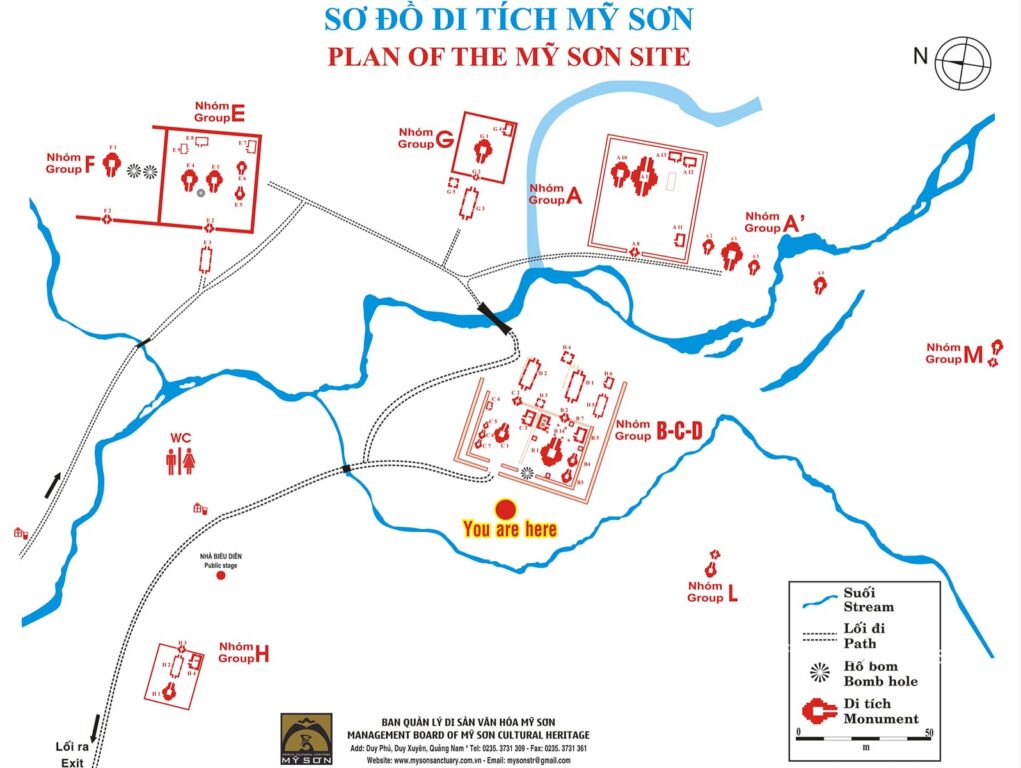

Henri Parmentier, the French scholar who conducted extensive studies of Mỹ Sơn in the early 20th century, classified the temples into 14 groups based on their location (map of the groupings above). Each temple group contains a main temple, complemented by towers and auxiliary structures. Just after 7:00am, we started with our first group of structures, the BCD cluster, because it’s the best preserved and most impressive of the groups.

Within Group B is Kosagrha B5. A kosagrha is a construction, typically with a saddle-shaped roof, used to house the valuables belonging to the deity or to cook for the deity. This is why it’s also known as a fire house. The fire house symbolises the treasures and prosperity of the kingdom. The main door faces north, in the direction of the Wealth God, Kuvera. This structure was constructed in what’s called the Mỹ Sơn A1 style, in the 10th century. This style is regarded as the pinnacle of Champa architecture and art and is praised for its light, graceful, and elegant carvings.

Within Group C, there is a structure called Temple C1, which is the kalan of this group. A kalan is a brick sanctuary, typically in the form of a tower, used to house a deity. The entrance of C1 features two pillars with lotus carvings. This is a feature of the artistic style of the 11th and 12th centuries.

Within Group C, there is a structure called Temple C1, which is the kalan of this group. A kalan is a brick sanctuary, typically in the form of a tower, used to house a deity. The entrance of C1 features two pillars with lotus carvings. This is a feature of the artistic style of the 11th and 12th centuries.

The structures contain a lot of symbols that would have been of great significance to the Cham people here. One of the most important symbolic structures at Mỹ Sơn is the cylinder, called a lingam, mounted on a square pedestal, called a yoni. The lingam is an icon of the masculine power of Shiva, while the yoni symbolises the creative power of the goddess Parvati. Together, the structure represents the dualist worldview of the Cham as they believed in the creation of life through a combination of masculinity and femininity in the universe.

Other symbols prevalent throughout the site include the eight-handed dancing Shiva, lions, elephants, semi-divine beings, and various symbols of the natural world (leaves, flowers, etc).

We then walked to Group A. Unfortunately, many of the structures at Mỹ Sơn were bombed during the Vietnam War and the structures in Group A particularly suffered. Group A’s main temple, Kalan A1, was once the tallest and most impressive structure in the Mỹ Sơn complex, but it was largely destroyed. However, excavators were able to successfully recover the pedestal of Temple A10, featuring a large linga-yoni made from sandstone.

Temples in Group G were also heavily damaged during the war. The group was restored by Italian experts from 1997 to 2012. A stele at the site states that the temple was built by King Jaya Harivarman to worship his parents and the god Shiva, and to bring blessings to himself.

The most striking characteristic of the main temple is the carvings of 52 terracotta kala masks. In Hinduism, kala represents an incarnation of the god Shiva, symbolising destruction, impermanence, and the ever-changing nature of the world. Additionally, at each of the four corners of the base, there are sandstone statues of lions.

We then moved on to Group E. Temple E1, the Kalan of Group E, was destroyed during the war. This temple was built during the early period of Mỹ Sơn when the construction technique had not been fully developed yet. As a result, it was not very tall. Its name is used for the earliest style of architecture at Mỹ Sơn complex. Temple E7 underwent reconstruction, so you can see how it may have looked like hundreds of years ago.

Right next to Group E is Group F. The bomb craters characterise this area throughout the grounds. Temple F1 is among the earliest structures constructed at Mỹ Sơn Sanctuary. It is currently in a state of despair. Group F was covered with soil and rocks due to the carpet bombing in 1969, and F1 was the temple chosen for restoration and archaeological work in 2002. The restoration team used mechanical equipment to excavate and remove the covering layer. However, when all the rocks covering it were removed, the bricks of the temple collapsed, resulting in what it looks like today.

Right next to Group E is Group F. The bomb craters characterise this area throughout the grounds. Temple F1 is among the earliest structures constructed at Mỹ Sơn Sanctuary. It is currently in a state of despair. Group F was covered with soil and rocks due to the carpet bombing in 1969, and F1 was the temple chosen for restoration and archaeological work in 2002. The restoration team used mechanical equipment to excavate and remove the covering layer. However, when all the rocks covering it were removed, the bricks of the temple collapsed, resulting in what it looks like today.

We spent about two hours exploring the complex. Because I was taking everything in I didn’t have any questions and so we moved on from site to site faster than perhaps I would’ve liked. I would love to revisit, but this time spend at least three hours digesting all the history! Nonetheless, it was incredible to see an amazing civilisation in such a beautiful setting. The area was clearly chosen on purpose by the Cham people, it really inspires spirituality.

We said goodbye to Mỹ Sơn and continued our journey north. We reached the Hải Vân Pass after an hour and a half. The pass is a very famous road in Vietnam, popular with motorcyclists because of the fantastic viewpoints. In the 15th century, this pass formed the boundary between Vietnam and the kingdom of Champa. Until the Vietnam War, it was heavily forested. At the summit is a bullet-scarred French fort, later used as a bunker by the South Vietnamese and US armies.

We said goodbye to Mỹ Sơn and continued our journey north. We reached the Hải Vân Pass after an hour and a half. The pass is a very famous road in Vietnam, popular with motorcyclists because of the fantastic viewpoints. In the 15th century, this pass formed the boundary between Vietnam and the kingdom of Champa. Until the Vietnam War, it was heavily forested. At the summit is a bullet-scarred French fort, later used as a bunker by the South Vietnamese and US armies.

We drove down the mountain and arrived at Lập An Lagoon, a lagoon within the Lang Co Bay and surrounded by the Bach Ma Mountain. The lagoon is famous for oysters, so we decided to stop here for lunch. There are a couple of very touristy spots along the lagoon and while we were sceptical, we knew we needed to eat! We sat down, ordered some oysters and spring rolls, and enjoyed the view. However, within a few minutes, it was pouring rain! We laughed as all the tourists out by the water ran into the cafe. It was a nice stop nonetheless.

We drove down the mountain and arrived at Lập An Lagoon, a lagoon within the Lang Co Bay and surrounded by the Bach Ma Mountain. The lagoon is famous for oysters, so we decided to stop here for lunch. There are a couple of very touristy spots along the lagoon and while we were sceptical, we knew we needed to eat! We sat down, ordered some oysters and spring rolls, and enjoyed the view. However, within a few minutes, it was pouring rain! We laughed as all the tourists out by the water ran into the cafe. It was a nice stop nonetheless.

An hour and a half later we arrived in the south of Huế where the extravagant and often glorious mausoleums of the rulers of the Nguyen Dynasty (1802–1945) are located. The Dynasty began in 1802 when Emperor Gia Long founded it and moved the capital from Hanoi to Huế in an effort to unite northern and southern Vietnam. Each Nguyen ruler has an extravagant tomb, and they are spread out along the banks of the Perfume River.

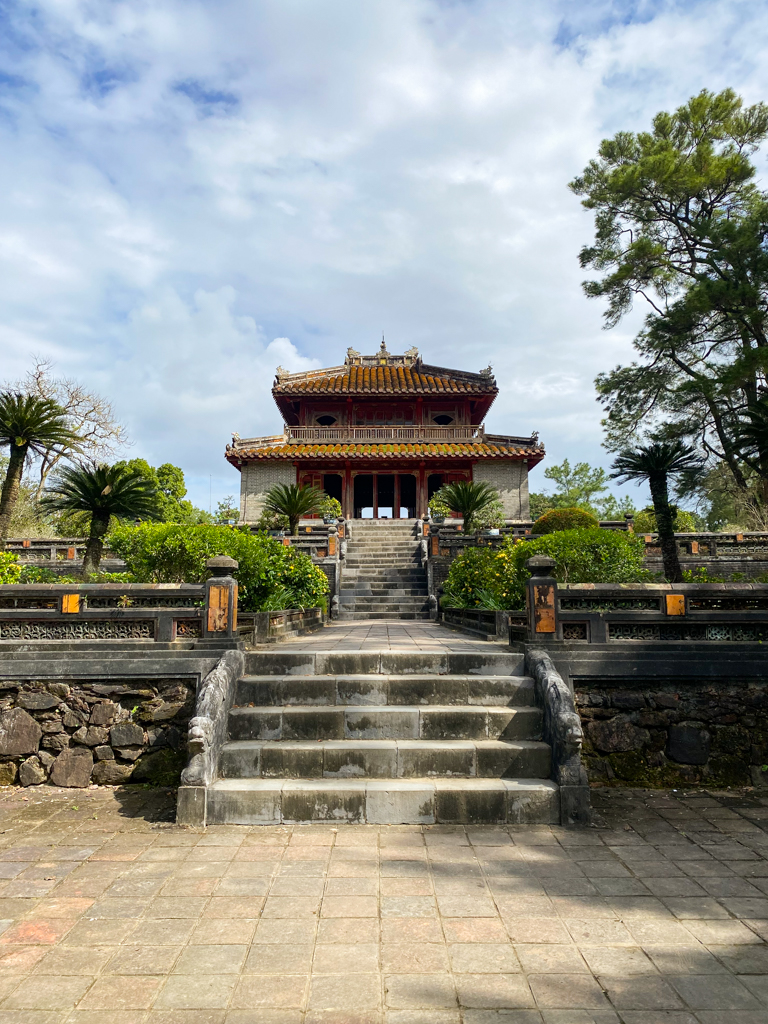

We started with Lăng Minh Mạng (the Mausoleum of Emperor Minh Mang). Planned during Minh Mang’s reign (1820–1840) but built by his successor, Thieu Tri, this majestic tomb, on the west bank of the Perfume River, is renowned for its architecture and sublime forest setting.

We started with Lăng Minh Mạng (the Mausoleum of Emperor Minh Mang). Planned during Minh Mang’s reign (1820–1840) but built by his successor, Thieu Tri, this majestic tomb, on the west bank of the Perfume River, is renowned for its architecture and sublime forest setting.

As for Minh Mang, he was the second ruler in the Nguyen Dynasty, one of Gia Long’s sons. Minh Mang was known for his scholarly nature and as an intellectually oriented monarch. He was known for his attention to detail and micromanagement of state affairs. As a result, he was held in high regard for his devotion to running the country. Our guide appeared to paint him in quite a positive light with an aligned view of traditional, Vietnamese pride and culture. And, like his father, he had an isolationist, anti-West view, and strongly believed in Confucian policies. This is perhaps why Ming Mang is looked on more favourably than later emperors.

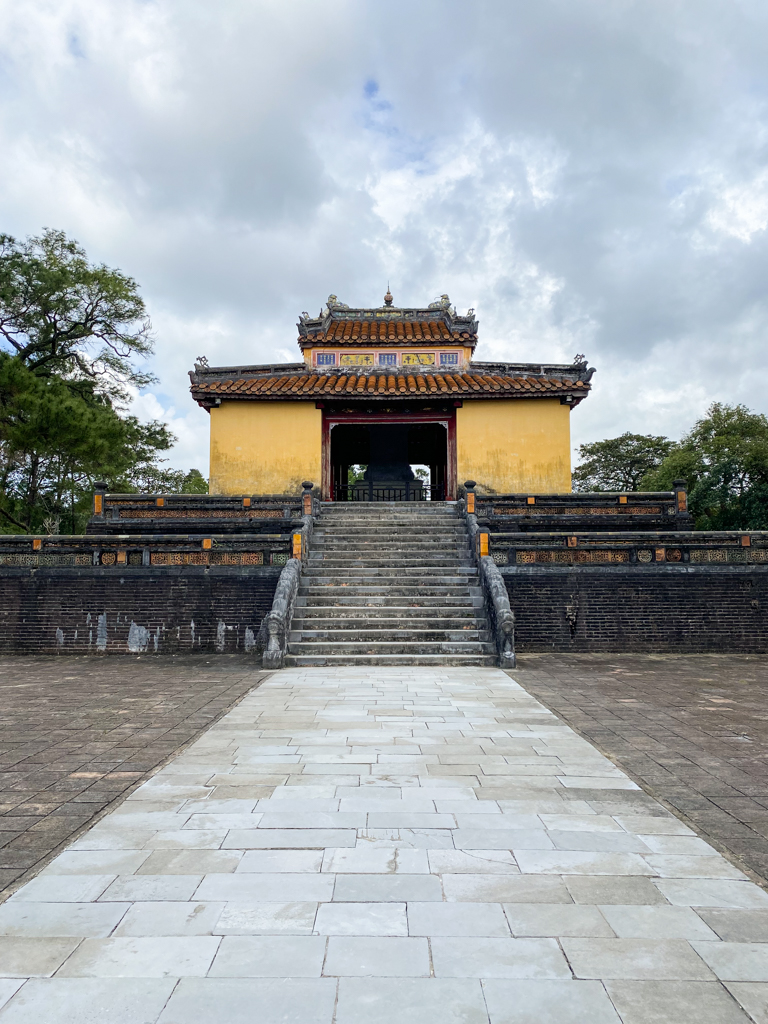

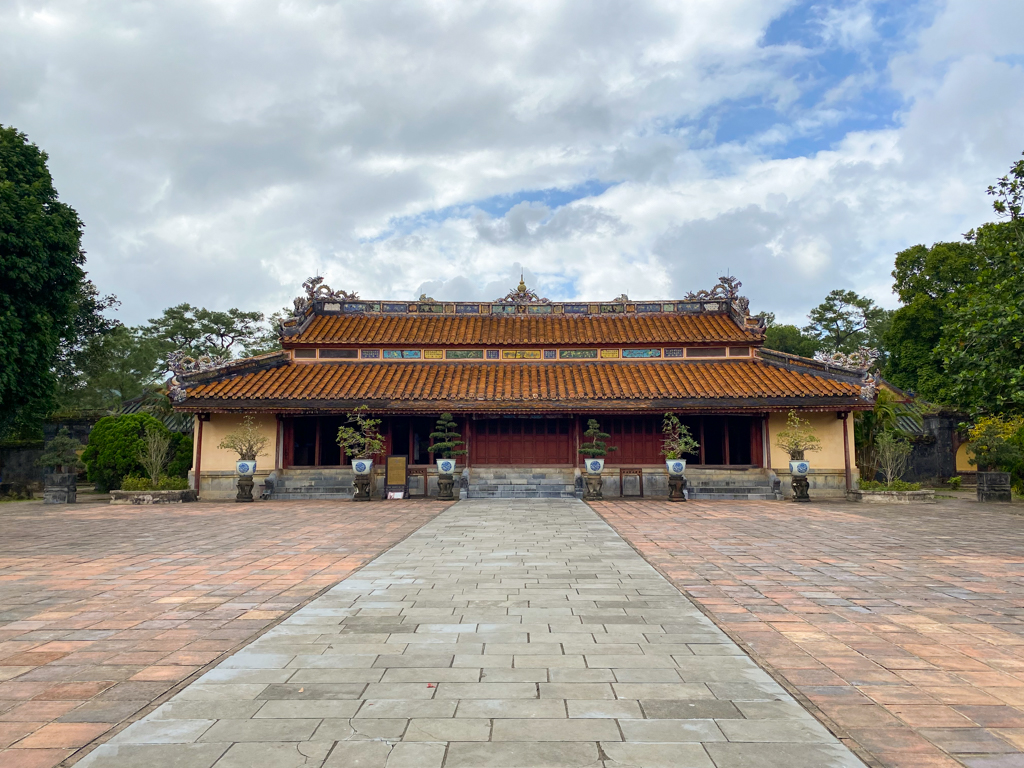

We first arrived at the Honour Courtyard where three granite staircases lead to the square Stele Pavilion (Dinh Vuong). Once we went up, through and down the pavilion, we arrived at another courtyard with the Sung An Temple, dedicated to Minh Mang and his empress.

On the other side of the temple, three stone bridges span Ho Trung Minh (Lake of Impeccable Clarity). The central bridge was for the emperor’s use only. We then reached Toa Minh Lau (Pavilion of Light), which stands on the top of three superimposed terraces representing the ‘three powers’: the heavens, the earth and water.

From a stone bridge across the crescent-shaped Ho Tan Nguyet (Lake of the New Moon), a monumental staircase with dragon bannisters leads to Minh Mang’s tomb. The gate to the tomb is opened only once a year on the anniversary of the emperor’s death.

We left Lăng Minh Mạng for another beautiful, but very different, tomb, Lăng Khải Định (Mausoleum of Emperor Khai Dinh). Khai Dinh was the penultimate emperor of Vietnam, from 1916 to 1925, and widely seen as a puppet of the French. Because of this, Khải Định was very unpopular with the Vietnamese people. Emperor Khải Định’s unpopularity reached its peak in 1923 when he authorized the French to raise taxes on the Vietnamese peasants, part of which was to pay for the building of his palatial tomb, and which caused a great deal of hardship.

We left Lăng Minh Mạng for another beautiful, but very different, tomb, Lăng Khải Định (Mausoleum of Emperor Khai Dinh). Khai Dinh was the penultimate emperor of Vietnam, from 1916 to 1925, and widely seen as a puppet of the French. Because of this, Khải Định was very unpopular with the Vietnamese people. Emperor Khải Định’s unpopularity reached its peak in 1923 when he authorized the French to raise taxes on the Vietnamese peasants, part of which was to pay for the building of his palatial tomb, and which caused a great deal of hardship.

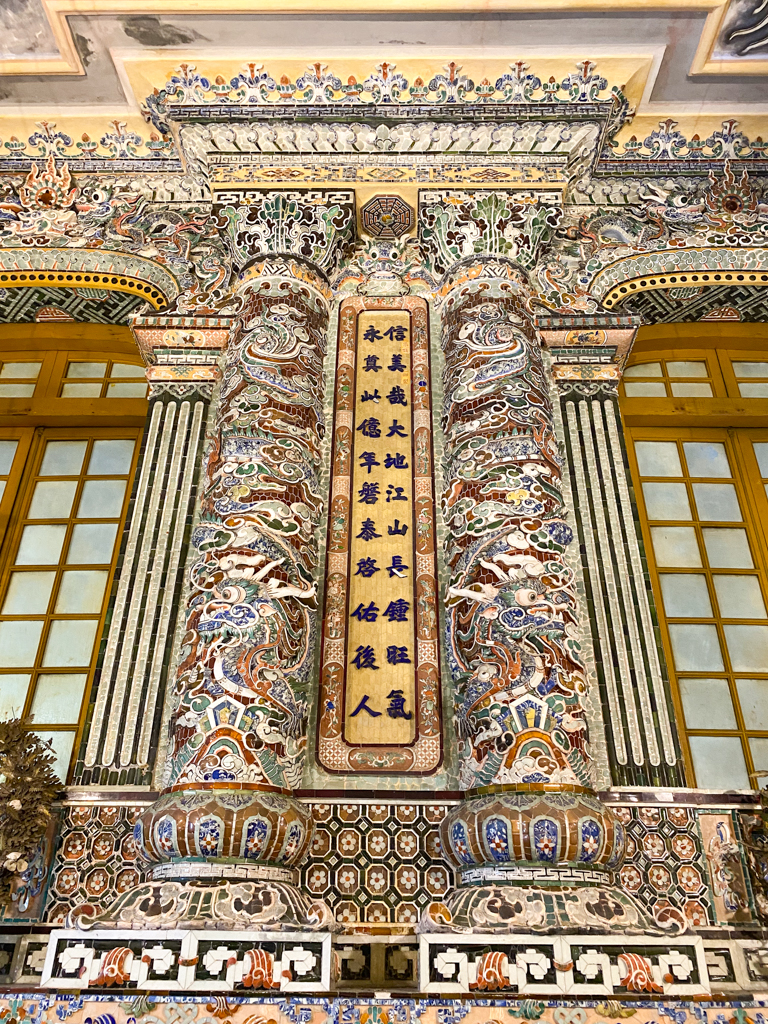

It took 11 years to construct his flamboyant tomb. The tomb is a synthesis of Vietnamese and European elements, so it has an almost gothic feel to it. Steps lead to the Honour Courtyard where mandarin honour guards again have a mixture of Vietnamese and European features.

Up three more flights of stairs is the stupendous main building, Thien Dinh. The walls and ceiling are decorated with murals of the Four Seasons, Eight Precious Objects and the Eight Immortals. Under a graceless, gold-speckled concrete canopy is a gilt bronze statue (cast in Marseilles) of Khai Dinh. According to historians, he suffered from poor health and was a drug addict, eventually succumbing to tuberculosis. His remains are interred 18m below the bronze statue.

We left the mausoleum complex at around 2:30pm to go to Huế. Once we arrived in the city it did take our driver and tour guide a while to find our place, but they called the accommodation and our host met up with us. We said goodbye to our driver and tour guide, who were so incredibly nice and gracious all day long.

Because we had a small lunch we went out early for dinner. We went to Maison Trang. They serve what’s called Royal Cuisine. When the Nguyen Dynasty relocated to Huế, the Emperors basically commissioned a new cuisine. Vietnam’s finest chefs were hand-picked and transferred to Huế to create new dishes. The chefs adapted traditional local dishes by introducing new regional flavours and textures for Vietnamese royalty. Perhaps the most distinctive feature of the food of the Imperial Court was a much greater emphasis on presentation. One category of these delicate dishes is royal rice cakes. At Maison Trang, we ordered three types: (i) bánh bèo (served in small dishes and topped with dried shrimp, crispy pork skin, and scallion oil), (ii) bánh nậm (steamed in banana leaves) and (iii) bánh bột lọc (filled with whole grilled shrimp with the shell on). They were all so incredibly delicate and yummy. We also ordered banh khoai, a crispy, fried-filled pancake that’s smaller and denser than banh xeo pancakes. It was crunchy and really flavourful.

And so ended our epic day of travel and touring. We had quite the day, so we turned in early for the night to prep for our next two days in Huế!

Do you like historical sites? Would you visit Mỹ Sơn or the Nguyen tombs?

No Comments